Why Ukraine will not lose independence

If Vladimir Putin knew what I know he wouldn’t have invaded Ukraine, he’d have left his troops to complete their military ‘exercises’ on the border and left it at that. But instead he pushed the boundaries, seeing how far he could go.

When the West said it wouldn’t defend Ukraine with boots on the ground or bombs from the air he’d already won. But for reasons we may never know he launched a full-blooded invasion with tanks, artillery, air strikes, missiles and up to 150,000 troops.

Some people cannot watch the horrific images used in newscasts: the shattered cities, towns and villages, battered residential and commercial buildings, rubble-strewn roads. Worst of all the needless loss of life: devastating, indiscriminate and unforgivable. The over-used description ‘war crime’ doesn’t begin to describe the horror.

Ukraine got its first hint that independence might be possible in 1985 when reform-determined Mikhail Gorbachev became General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The new leader introduced his revolutionary policies of Glasnost, or openness, leading to a free press and freedom of speech, and he attempted to streamline the clunky Soviet economy by ‘decentralising’ decision making with what was called Perestroika or restructuring.

After the Berlin Wall was breached in 1989, Communism imploded and Ukraine saw that its long-awaited independence would come soon. Soon after it arrived in 1990, I was part of a Foreign Office Know-How Fund established to help the population of what was then the world’s newest independent country better understand how business and commerce worked in the West, where since 1945 competing economies had made for a free, peaceful and affluent Europe.

That’s when I took the picture above. In the strategically-important naval base city of Sebastopol, a retired gentleman reads his newspaper ignoring four women of a similar age who are busy gossiping.

Putin’s invasion is particularly harrowing for me when I see the ruined streets of Kiev and Kharkov, streets I once walked with Ukrainian friends, colleagues, aspiring business people with ambition, ideas and energy. I remember seeing one street on the television news now all but impassable which I used to reach a hospital where some of the child victims of Chernobyl were being treated. Independence meant much to Ukraine. I was there when elections brought the first president Leonid Kravchuk to power.

You could see the passion of freedom on every face, the hope and aspiration, the spirit and determination to break from the rigid restraints of Communism.

For centuries Ukraine has been treated as subservient to Moscow’s ruling powers, not just before Putin’s invasion began on February 25, 2022, and not only since the Soviet revolution of 1917. Perhaps the worst thing to happen in Ukraine was in the 1930s when Joseph Stalin forced the adoption of Collective Farming, ensuring compliance by effectively starving the farming community to death.

Years later, when one of Stalin’s successors, Nikita Khrushchev, was asked how many died he said ‘we never counted them.’ It is estimated to be between three and a half and four million.

When farming recovered, Ukraine’s farms fed the Soviet Union, its factories built aircraft, tanks, lorries and tractors. Its men joined the ranks of the Red Army, the navy and Air Force. In the last days of Communism they frequently weren’t paid, sometimes they never knew when they were coming home and during the abortive conflict in Afghanistan some didn’t. But when Communism began to release its iron grip, schoolchildren still had to attend classes in political studies. ‘They made us go, but they couldn’t make us listen’ a Russian Air Force veteran told me.

Ukraine is the second largest country in Europe; only Russia is bigger. Its first 32 years of independence has been hard with progress hampered by Soviet legacy, inadequate infrastructure, old equipment, an untrained labour force, a shortage of investment and, sadly, corruption.

Before he ordered his invasion, the one-time KGB officer that is Vladimir Putin saw Ukraine as a ‘colony’ run by ‘puppets’. He knows now he was wrong; Ukraine is nobody’s colony, its president Volodymyr Zelensky may be a former comedian, but he’s not a puppet and has demonstrated extraordinary leadership qualities.

Vladimir Putin cannot win the battle he started; things have not gone well. Russian casualties have been high, Ukrainian resistance strong. Some Russian troops have divided loyalties and don’t want to fight people they see as their own. TV images showed Russian troops hiding in Ukrainian gardens, and I’ve heard stories of them getting their orders and weeping.

If Putin ends up ruling Ukraine with a Moscow-appointed president, he will never rule the 44 million people. Having waited centuries for independence, they will never give up the freedom the collapse of Communism presented.

Earlier Blogs

School is very different to what it used to be. In my day the teachers were either incompetent, war heroes or psychopaths, sometimes a bit of all three. If you didn’t learn by rote, you were beaten with a variety of instruments and different degrees of brutality.

In my church school those that failed to learn the Collect for the Day from the Book of Common Prayer were sentenced to three strokes across the open hand with a rattan cane. Repeated disobedience was punished with a number of strokes across the buttocks, but bare flesh was never exposed, at least not in front of the class.

The number of strokes administered was related to the gravity of the misdemeanour. Getting caught putting pastels into a girl’s inkwell brought three strokes, answering back five, bad language arising from a lost temper up to ten.

Worst of all was to be sent to the head’s office where waiting to be punished was frequently worse than the punishment itself. The late film director Alfred Hitchcock, who attended St Ignatius’ College, at that time in North London’s Stamford Hill, said he learned about suspense while awaiting stokes from a ‘tolly’, traditionally a whalebone wrapped in leather, but later a piece of leather about a foot long shaped like the sole of a shoe.

When I read that in 2017, 4,362 criminals had applied to become teachers, I wondered if today’s classrooms were any better than they were in my day. The figures, 26% higher year-on-year, came from the Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) thanks to a Freedom of Information Act enquiry from The Knowledge Academy.

Unfortunately, the DBS didn’t know how many of the criminals they revealed had landed teaching jobs. Given that the most common crime was ‘driving with excess alcohol’, which accounted for 1,282 of the total, probably quite a few.

The remaining 3,080 offenders included rapists, paedophiles and drug dealers. In descending order, burglary came up 229 times, crimes mentioning the word ‘violent’ 157; there were 26 racially motivated incidents while 12 crimes resulted in death.

Of the 32 sexually motivated crimes, seven involved children under 16. Crimes involving children, including assault and neglect, totalled 43, a 169% increase over the 2016 figure. Drug related crimes were up 35% year-on-year, sexually motivated crimes were 23% higher. The number of burglaries fell 16%.

These sobering statistics made me look more closely at the alleged views of Charles Heinrich, former chairman of the Boarding School Association who is head of the fee-paying Cumnor House Sussex school in Haywards Heath. He thinks that children should learn to play poker and that a number of lessons can be learned from the game. I don’t doubt that there are lessons to be learned from the mental side of playing cards and poker can be challenging, but I’m not sure that school is the right place to teach them.

A champion poker player called Liv Boeree has been quoted as saying: ‘If more children learned to play poker, they might be more ready for the real world. For instance, what is a poker hand other than a progressive set of decisions with consequences, sort of like adult life itself? Children would learn that their actions have consequences and the benefits of updating your beliefs.’

It reminded me of the Kenny Rogers song The Gambler that says ‘you’ve got to know when to hold ‘em, know when to fold ‘em, know when to walk away.’ I don’t know how some children would handle the fifth verse:

‘Every gambler knows that the secret to survivin’

Is knowin’ what to throw away and knowin’ what to keep

’Cause every hand’s a winner and every hand’s a loser

And the best that you can hope for is to die in your sleep.’

Britain is not experiencing its finest hour. A government in office, but not in power, an Opposition unable to balance ideals with pragmatism. Not only are we lacking leadership, but also ideas and vision.

In terms of the economy, Britain is the world’s fifth largest. But once we’ve kept the head of the NHS above water and returned the cash to the retired that they’ve been paying in all their working lives, it appears there’s insufficient left to put roofs over the heads of our population, for education or policing.

Those who support our divorce from the European Union believe the economic uncertainty that will inevitably follow will be worth it because long-term the country will be better off on its own. Time will tell. Far from getting our country back from Brussels, some believe the reins will be taken over by United States.

Others are convinced we’re heading for a dystopian future. They’ve read the novels: George Orwell’s 1984, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1931), Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1953), Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange (1962), Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (2006) and Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1986). They’ve seen the movies: The Matrix (1999), Minority Report (2002), Children of Men (2006) and The Hunger Games (2012. My favourite is Ridley Scott’s 1982 Bladerunner.

Recently I had to overnight in Bristol and was booked into the £180 a night Holiday Inn Express, a 15-minute drive from the city centre. I’ve stayed in Holiday Inns in different parts of the world and have always been comfortable, if not at home. When I worked briefly in Glasgow I even lived there (my dry cleaning bill was horrific).

But the Holiday Inn has changed, at least it has in Bristol. The reception staff reeled off the mantra about parking as if they were robots. They recited the script perfectly, but unless you reacted, they started again as if the words were in a loop.

Everything was spotlessly clean and functional, but so devoid of character that an abandoned lump of lard is more interesting. Perhaps it was me: a long drive relying on a SatNav which tells you where to go, but doesn’t say where you are.

My room was what you expect from Holiday Inn. Noticeably smaller than usual perhaps, but complete with the usual accessories: ironing board and hair driver. Essential for some, but never used by me.

The dining area at breakfast was an even worse experience than reception. There was no noise, no buzz of conversation, no rattling of crockery. Going by their appearance and speech, people drawn from all over the planet moved with a controlled deliberation, as if contact with any other guest was forbidden. Not robotic, but it could have been.

Breakfast was close to automation. Food on hot plates under metal hats. The coffee machine pinged, the toast dinged. If a latter day Michelangelo had checked in, the scrambled eggs could be sculpted into something yellow and beautiful. The bacon didn’t taste if it had once belonged to a pig. Everything else was in plastic pots, airtight glass or plastic wrapping that both defied germs and denied access to all but circus strongmen.

A member of staff, identified by her uniform, arrived to replenish the coffee machine. She was pretty, East European with a winsome smile. Neither a robot nor a zombie. When I shared my observations she roared with laughter, a spontaneous human reaction that lifted my spirits; she also agreed with me.

I believe people are wrong about Britain moving inexorably towards a dystopian society? We’re already there. It’s not dystopia tomorrow, but dystopia now.

There are not enough coffee machine replenishers like the one I spoke to. Although he may not be universally popular, Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson is at least a human being, flawed like the rest of us. Listen and look at some the others in Westminster. They may not be zombies or robots, but some of them are beginning to sound like them with their ever-repeated sound bites that don’t answer the question put. There are people who call the prime minister Bot.

Mine is a generation in decline, and the sooner it disappears the better. It has looked after itself with inflation-linked pensions and escalating house prices that have turned modest suburb dwellers into millionaires. At the same time it has shafted subsequent generations with longer working lives, unaffordable property, either to rent or buy and, for many, nothing to look forward to beyond the minimum wage.

Although environmental consciousness appears to be a mantra at Whitechapel’s Qbic Hotel, which describes itself as ‘greenest hotel in London’, the reality owes more to marketing, and quirky marketing at that.

Although environmental consciousness appears to be a mantra at Whitechapel’s Qbic Hotel, which describes itself as ‘greenest hotel in London’, the reality owes more to marketing, and quirky marketing at that.

How else can you explain pig and dairy cow shaped boxes in the dining room and plastic hands as coat hooks on the back of bathroom doors? The rooms have no wardrobe, but an open clothes hanging space built into a wooden frame inspired either by medieval torture or a sex parlour restraints room.

As you can see above, the TV is bolted to a plank of wood at the bottom of the bed, while a tangle of heavy duty plastic, that might have once driven an electric lawnmower, has been mangled into a shape resembling a table lamp. That’s the weird contraption pictured between the chair and TV. I have no idea how it’s turned on.

A mirror has been eased between the upper rungs of a rickety wooden step ladder with its one short leg levelled up with a wedge. While this suggests recycling, the gadget is duplicated in every room that I’ve seen, so the truth is different.

On the wall is a difficult-to-read legend that bangs on about the environment, notably the shower, which although it works better than some, doesn’t seem different, although the management describe it as a rain shower that uses a water and air system that reduces the quantity of water used.

Each room claims to include a perfect bed, but they may mean a perfect mattress, hand made in Devon from natural ingredients including organic lamb’s wool and horse hair. I slept well enough, but I invariably do. It may have improved my snoring, but not by enough to wake me.

The common areas are equally eccentric. There are bicycles or parts of bicycles in various places. In reception, for instance, one with a sidecar is used as a check-in desk, while another becomes a resting place for a vast bouquet of flowers.

In the lifts there are handrails, probably designed for purpose, but they look as if they were intended for inner-city crowd control.

While functional, the dining room/bar/lounge, with its cocktail of seating arrangements, is prone to overcrowding. It’s also littered with boot sale boxes and decorated with white tiles that make the walls look like public toilets or Turkish baths.

Perhaps the most significant gesture to the environment is the building. For instead of designing a new one, the Qbic converted a disused office block on Adler Street, a stone’s throw from Brick Lane, and for this alone the hotel deserves the awards they’ve won for their ecological efforts. It also means that the landlord has been getting an income since the hotel opened in November 2013.

Customers are asked to show their respect for the planet by recycling waste and the management invites them not to insist on clean towels every day. Some of their environmental claims may be questionable, even dubious, but this budget hotel is at least different and the staff are both friendly and efficient. There’s a sister hotel in Amsterdam and I’d like to try that one day.

Thanks to several singer-songwriters and various folk-rock specialists, the banjo has emerged from its dark days of ridicule and condemnation. At least that’s what I thought until I saw that Torbay Council has decreed that the sound of the banjo in the Devon fishing town of Brixham is a statutory nuisance under Section 79(1)(ga) of the 1990 Environmental Protection Act.

Thanks to several singer-songwriters and various folk-rock specialists, the banjo has emerged from its dark days of ridicule and condemnation. At least that’s what I thought until I saw that Torbay Council has decreed that the sound of the banjo in the Devon fishing town of Brixham is a statutory nuisance under Section 79(1)(ga) of the 1990 Environmental Protection Act.

After a number of complaints to police, busker Matt ‘Banjo Man’ Woffindale has been issued with a Noise Abatement Notice under Section 80 of the act which bans him from playing in the town centre. Some believe his all-weather playing in Fore Street exemplified the ‘sound of Brixham’, but these have been outnumbered by the complainers, many of them retailers who presumably think the banjo is no more than a frying pan with strings.

The ban is contrary to contemporary view. The instrument has recently been used in recordings by Eric Church, Taylor Swift and Kacey Musgraves, and its appeal has been broadened by exceptional players like Bela Fleck and Tony Trischka. The instrument has a regular place in the popular American group The Avett Brothers, while the London folk-rock group Mumford & Sons feature Winston Marshall on banjo.

I’ve never owned one. Although I’ve enjoyed novelty numbers, when the guitar player picks one up and chases up and down the keyboard earning lots of applause, it has never appealed, and the occasional peaks in popularity haven’t lasted long enough to change my mind.

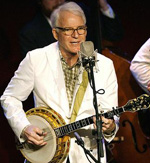

Bluegrass emerged in the 1940s when Earl Scruggs (pictured above) and his three-finger picking style effectively created a new kind of music. Scruggs, described as the Beethoven of the banjo, died in 2012, you’ll find a biography of him here and some late footage playing with others here.

If you haven’t heard of Scruggs you’ll certainly be aware of the 1972 film Deliverance with its Duelling Banjos. The tune the film uses was based on a 1955 song, the Feudin’ Banjos which owed a lot to the folk ballad Yankee Doodle whose origins go back to the American Revolution. Go here to see the footage from the movie.

Later there was the Grammy-winning music from the Coen Brothers movie O Brother, Where Art Thou starring George Clooney. Released in 2000, the soundtrack, which features the banjo, kickstarted a revival more enduring than its predecessors.

So says banjo manufacturer Greg Derring. He was keen to recreate the sounds of the Kingston Trio, so in 1963, he paid $20 for his first banjo. Twelve years later he and his wife Janet formed the Deering Banjo Company which has since produced 76,000 banjos making it the instrument’s biggest US manufacturer.

The instrument’s halcyon days began with the minstrel shows of the late nineteenth century, long before amplification, when the banjo held down a rhythm that all the band could follow. But technology and the more versatile guitar gradually pushed it into near obscurity.

Banjos are believed to have developed from the gourd-based instruments brought to the US by slaves. According to banjo historian Robert Lloyd Webb, by the 1840s the instrument had reached the form we know today, that is with four, five or strings tightened over a membrane that acts as a resonator.

Actor-comedian Steve Martin, pictured above, who often featured the banjo in his days as a stand-up comic, is not only good enough to have played with Earl Scruggs, but he also sponsors the Steve Martin Prize for Excellence in Banjo and Bluegrass. Times have changed, and after years in the doldrums, this once music hall joke is now almost respectable. Unless you live in Brixham.

When I’d finished my first visit to Screwfix and paid over the odds for more nuts and bolts than I wanted, I thought how much the company and its procedures owes to the Two Ronnies and the wonderful fork handles sketch.

Shopping at Screwfix involves the same procedure as Argos in that you wade through a chunky catalogue until you find the widget you’re looking for, write down its stock reference number and when it’s you turn in the queue hand it over the counter. The staff, carefully selected for having absolutely no interest in what they’re doing, either pad away and get it off the shelf or come back empty handed, shrug their shoulders and say it will be in tomorrow.

Speaking is minimal, so those behind the counter can easily get through the day with less than 20 words of basic English, a useful advantage in today’s job market.

It makes me nostalgic for those big old hardware shops that always had at least one of everything right down to the left-handed widget with a Whitworth thread. Not only that, the person serving knew exactly where to find it in a dusty labyrinth of what looked like disorganised shelves. Those were the days of the fork-handles-four-candles brilliantly satirised by the Two Ronnies.

As the world changed, margins got squeezed and the accountants moved in. The first thing they did was reduce stock and sell off all the left-handed widgets whatever thread they had. If they sold only one a year they would no longer stock them.

These days, you can still get the widget, but now they’re badly made in China and fall to bits in two years. The thread is as far away from Whitworth as Beijing, and instead of one that used to last a lifetime, you have to buy an expensive box of 50.

Those days will never come back and following the death of Ronnie Corbett in March and Ronnie Barker in 2005, neither will the Two Ronnies.

For the record, Screwfix was founded in 1979 as the Woodscrew Supply Company, but 20 years later was acquired by Kingfisher, owners B&Q. Today, with over 11,000 items in stock, Screwfix is the UK’s largest multi-channel retailer of trade tools, accessories and hardware products.

It has helped make Kingfisher the largest home improvement retailer in Europe, and with over 1,176 stores in 11 countries across Asia and Europe, the third-largest in the world.

Kingfisher was formed in 1982 when Paternoster acquired Woolworths in a deal that included B&Q, at that time a relatively insignificant chain of home improvement stores. Kingfisher pumped money into B&Q and the group grew rapidly, going on to takeover Comet and Superdrug.

At the turn of the century, Kingfisher decided to focus on home improvement, demerged Woolworths, whose days were immediately numbered, and sold Superdrug.

A recent restructuring brought it closer to the French DIY chain Castorama, whose boss Véronique Laury became Kingfisher’s chief executive forcing her predecessor Kevin O’Byrne to leave. It’s a pity, but Quatre Candes and Poignées de Fourche hasn’t got the Two Ronnies ring.

When Chernobyl blew in 1986, there was a party of English schoolgirls staying in nearby Kiev. I was on the Daily Mirror then and remember driving down to Ashford and meeting them at Lydd Airport in Kent where Foreign Office officials were handing out iodine tablets as protection against the possible effects of radiation.

Soon afterwards I was told that three days before the power station suffered its disastrous radioactive leak, all the bees in the area left. This wasn’t true, but after the explosion, bees for miles around wouldn’t leave their hives. We know now, but didn’t know then, that bees avoid areas where radiation levels are high.

It intrigued me that bees may be able to detect things human beings need scientific instruments to find and since then I’ve been so fascinated by these insects that a hive has finally been installed in the field at Lanlivery.

For centuries we have exploited bees with little or no thought. They seem unaware of this and continue working tirelessly within their own complex society, producing honey which we recover from their hives and put into jars which end up on the supermarket shelf or at the farmer’s market.

In the late spring I went on a bee safari. This involved visiting six beekeepers in the Roseland, that part of Cornwall’s south coast that runs from Gorran to St Mawes. It was a warm day and a beekeeper’s protective clothing is the last thing you’d want to wear because they restrict movement and make you hot and uncomfortable. The veils vary in design, but I found it disconcerting every time an angry worker bee crashed into the mesh in front of my nose.

The purpose of the safari was to inspect the hives for the standards of husbandry, to find the queen and, where appropriate, mark her so that the beekeeper will know how old she is. Everything about this exercise suggested a need for calm and gentleness. How wrong I was. On two occasions one of the inspectors dropped the frames he had drawn from the hive. No apology came either to the beekeeper or the bees who were scratching about in the grass desperate to get home.

Someone was always standing by with a smoker, a cross between a coffee pot and oil can with bellows attached. It is stuffed with hessian and wood chips which when lit produces smoke which calms the bees. This has been known for centuries, but no one understands quite why.

I felt uncomfortable as the experts worked almost as if the bees weren’t there. As the frames on which the eggs were laid were removed from the opened hive, the inspectors seemed both oblivious to the increased volume of buzzing and the more frenzied movements through the air.

There have been many stories about the declining bee population and the threat this presents to agriculture. It has been suggested that agricultural chemicals, pesticides and fungicides, are responsible as these contaminate the pollen that the workers collect to feed their hives. The varroa mite is the threat we’ve heard most about in Britain. This is an external parasite that attaches itself to bees and sucks their blood, weakening them and shortening their lives. They look like ticks, about the size of a pinhead and are easily visible.

We saw some on the safari. There are a number of treatments for varroasis which make the mites die and drop off. The success or otherwise of the treatment can be measured by the number of corpses dead at the bottom of a hive.

*****

The Fattoria Mose sits high above a village close to the south coast of Sicily, three kilometres from the sea and four from the island’s biggest tourist attraction, the Valley of the Temples, oddly named because they aren’t in a valley at all. Sicily has many secrets, but Fattoria Mose shouldn’t be one of them.

In many ways the island is the fulcrum of Mediterranean history, taking in everything from the irascible, but brilliant Carthaginian commander Hannibal, who might have found the inland mountains above a challenge, to the deal the Mafia did with the Allies to smooth the landing of the Eighth Army at Gela in 1943. Sandwiched between were conquests by the Greeks, Carthaginians and Romans, and invasions by the Byzantines, Saracens, Normans, Germans, Angevins, Spanish and others. When Giuseppe Garibaldi landed at Marsala in 1860 he defeated the Bourbons and chose Sicily to launch his campaign for the unification if Italy.

Nearest town to Fattoria Mose is Agrigento, a rambling community dominated by ugly apartment blocks, noisy by-passes and a port. Like Villaggio Mose, with its Burger King and McDonald’s, it’s best avoided.

Technically a 200-year-old manor house, Fattoria Mose from some angles looks like a small castle with vaulted entrances, steep staircases and high ceilings where massive bureaus get lost among masses of books, mirrors, obscure paintings and family photographs.

Built in the 18th century, when Villaggio Mose comprised nothing more than a sulphur mine and accommodation for the miners, it has its own chapel and today is home to a raft of affectionate cats and somnolent dogs dozing in the heat. It is both the home of the Agnello family and a working farm producing oranges, almonds, pistachios, fruit, vegetables, wheat and, notably, olive oil.

Although the house can currently accommodate eight, in 1997 the old stables were converted into six self-catering apartments the largest of which sleeps six. There are three four-person apartments and two for couples. Those that want to gather in the evening to eat alfresco a variety of authentic local dishes cooked with home-grown ingredients and washed down with copious quantities of wine. Conversations in many languages cross back and forth over the dining table while cicadas dominate the background and the cats purr on the laps of the guests that will have them.

Presiding over this ever-changing gated community with a calm, worldly grace and easy smile, although not without a hint of sadness, is Chiaro Agnello who when she is not taping away at her laptop, fills the kitchen with the astonishing aromas of Sicilian cuisine. Worth visiting for that alone, but if you’re anywhere nearby not to be missed. Follow this link: www.fattoriamose.com

*****

My relationship with department stores has been uneasy since as a badly behaved toddler I wandered away from my mother and got lost in Selfridges.

I remember on countless other occasions being dragged round Jones Brothers in Holloway Road, which was closed in 1990 and is now a home for Waitrose. Then there was John Barnes in Finchley Road, closed in 1981 now also a Waitrose. Later there was Bentalls in Kingston-upon-Thames. My mother liked department stores, I didn’t.

The Selfridges issue was resolved one lunch time not so long ago when I was at Citywire in the far from salubrious back streets of Vauxhall. I took the Victoria Line to Oxford Circus and spent a fortune on underwear because the man on the telephone was the only one of many who made sense.

Although I’d written about Debenhams and spoken to them on conference calls, as a place to shop it wasn’t on my radar until I was snapping up some outrageously flamboyant, cut-price duvet covers in Canterbury and was persuaded to open an account to get an extra discount.

That relationship is now over and I will never darken the doors of its branches again. Nor will I use its credit card. There are three reasons for this extreme behaviour, four if you count their refusal to post my complaint on their website: inefficiency, stupidity and fraud.

With a middle-aged spread, or more accurately the colloquial beer gut, that is a 36-inch waist along with a duck-like 29-inch inside leg, jeans aren’t the easiest garments to buy on-line. An extensive web search showed that Debenhams had what I wanted in the size that I needed. When they arrived, the jeans were so good that I decided to buy another pair. That’s when the trouble started.

Although there are sophisticated logistics, computer programmes, bar codes and fail-safe devices to avoid errors, the Debenhams carrier decided that my Cornwall address was in Southampton. Having discovered that it wasn’t, instead of putting them on the correct run west, he returned the goods to head office. Debenhams then cancelled the order without telling me. Only when I chased it they did credit my account.

On its own this is insufficient for my boycott, but then came fraud. Among the predictable raft of Amazon stuff, obscure CDs, boxes of wine and restaurant bills, my monthly credit card statement included a series of transactions to Newflixhd, an outfit that supplies feature films. The payments were around £30 a month and went back to January 2014.

When I complained, the fraud department said my card details had been hacked. They cancelled the card and issued a new one. They also credited my account, although to avoid penalty charges I was advised to settle that month as I would be reimbursed the next. Not particularly customer-friendly.

Although the new card has not been used, it too has apparently been hacked as my last statement showed that Newflixhd had been at it again, billing me about £30 for every month since January.

I wasn’t put through to the fraud department this time. Do nothing, the call centre assistant said, and pay nothing. It will be sorted. We’ll see.

*****

There is no shortage of clichés that can be deployed to describe the varied characteristics of the nationalities of Europe. I have this German friend who classified countries on the basis of their eating habits. The Germans were the sausage eaters, the Italians the spaghetti eaters, the Spanish the paella eaters and the French the frog eaters.

Predictably the British were the pie eaters. I can only guess what he will make of Marks & Spencer’s new fish and chip pie: an all-butter short crust pastry crammed with lumps of cod, minted pea puree and béchamel tartare sauce topped with a chip lid covered in seas salt.

This bizarre gastronomic creation costs £3.49 and packs an impressive 581 calories which represents just over a quarter of a woman’s recommended daily intake and a little more than a fifth of a man’s. Marks & Sparks describe this horrendous sounding hybrid as a ‘classic traditional British dish’ turned into a pie.

Such an addition to the ready meals market might have attracted a welter of media criticism sprinkled with snide one-liners, but perhaps because Marks are generous advertisers, the press were restrained. Even the Daily Mail resisted the temptation merely adding a Marks’ quote that said the product, first made available in April 2014, was ‘specially handcrafted in Yorkshire. Each pie is lovingly created with top quality fillings made in small batches for a truly delicious taste of the seaside.’

I’m not sure what they mean by a taste of the seaside. Ice cream sprinkled with sand, sticks of rock that make dentists rich or candy floss that gets whipped away by the wind. Perhaps the Americans will like it. They have a weakness for unusual combinations, serving lobster, prawns or shrimp with steak, for example. This might have started in North America, but now ‘surf and turf’ has gone global.

But unless Marks & Sparks offer a helping hand, these intriguing mixtures are unlikely to catch on: bacon and grape jelly on toast, peanut butter and maple syrup on rye, bagels with Foie Gras, bananas with mayo or ketchup, toasted English muffins with cream cheese, bacon, French fries and brown gravy.

If Marks’ fish and chip pie establishes itself in the ready-made meals market, maybe they’ll be inspired by the English nursery rhyme ‘Six a Song of Sixpence’ and produce one with four and twenty blackbirds. That would destroy even the most slender of waistlines as well as defy definition by national characteristic.

*****

Cornish weather is more unreliable than an angry teenager, but less predictable. It is a sobering fact that up to seven weather fronts can pass across the county in any 24-hour period and after over a quarter of a century living here, I still haven’t got used to it.

While to the east the county butts into the rest of England, it is otherwise surrounded by water, which gives its climate a maritime feel. The north coast can be basking in brilliant sunshine and the surfers having the time of their lives, while the south suffers a windy deluge that turns umbrellas inside out.

Sparkling sunshine frequently brightens the shorter days of autumn and winter, but around Easter heavy grey skies may close in and it can train all summer, or appear to. Nothing can destroy the magical atmosphere of Cornwall, though, the vast stretches of sandy beaches or the warmth and humour of the inhabitants. So the tourists keep coming back and eventually even they are rewarded with spells of spectacular weather the memories of which can last a lifetime.

In some ways the fickle and occasionally stormy climate has shaped Cornwall’s history by keeping the miners underground, attracting smugglers, as it made detection less likely, and sent ships to the bottom of the sea giving rise to the notorious wreckers.

The higher than average rainfall means that Cornwall grows grass better than most places. Although this makes some of its golf courses excellent, the rough can be thicker and more than usually determined to conceal and possess balls straying from the fairway.

Other parts of the country have suffered worse than Cornwall this winter with people driven from their homes, their possessions destroyed and their cars written off with flood damage. Our last major storm was on 23 December 2013, which blew dustbins down the street. There has been plenty of rain since, bringing flood warnings as the ground was saturated and unable to absorb any more water. Parts of the country have got it worse. Roll on Spring.

St Awful takes a turn for the worse

There are good reasons why the Cornish often describe the county’s biggest town of St Austell as St Awful.

There are good reasons why the Cornish often describe the county’s biggest town of St Austell as St Awful.

As this is a long established, if not affectionate nickname, it is nothing to do with Richard Curtis’ latest movie, much of which was filmed there. Called ‘About Time’, the film has been so widely bombed that it could have only raised the volume of those who criticise the town.

Making the situation worse is the fact that St Austell has recently lost one of its few remaining assets. I’m referring to the closure and boarding up of the wonderfully unique Delmonicos, my favourite wine emporium, formerly run eccentrically by one of the town’s great characters, David Delmonico.

The ramshackle building has been on the market for some time and, despite the hard-working efforts of two of David’s children, Jason and Suzanne, the days of the off-license were numbered in 2009 when David lost his battle with lung cancer aged 69.

His shop was a remarkable place, a dingy Aladdin’s Cave, grubby and poorly lit, with straw on the floor, faded pictures on the walls, empty wine boxes under your feet and, half hidden on the shelves, the odd brilliant vintage at an affordable price, its label covered in grime. As well as supplying wine you couldn’t get anywhere else, you could buy honey, olives, Scrumpy and spectacular glasses that made good wine taste even better.

David’s heart and soul belonged in 1960s Swinging London, that and his addiction to French cigarettes probably did much to damage his lungs and liver. Apart from a gap in the middle, while he chased a lady or ladies round France, or so he told me, he ran the establishment for over 30 years.

He learned his trade from his father, who was descended from a Swiss family hailing from the village of Mairengo in the Ticino Canton close to Italy. The family name, originally Del Monico, has been associated with food and wine since 1824 when the former sea captain Giovanni De Monico opened a wine shop in New York.

A century later, a parallel London business was opened in Soho’s Old Compton Street, and it was there that David sharpened his taste buds, learned to judge a vintage by the smell of the cork and not only appreciated the difference between Margaux and Moet, but knew the optimum size of the bubbles in the bubbly.

His father sold the business in 1970 and David came to Cornwall with his wife Barbara and three children settling in St Columb to run a pub. But along with nicotine from the Gitanes, wine ran through his veins, and it wasn’t long before he opened in St Austell’s South Street making the town rather less awful than before.

David was not part of the retail establishment. Like Groucho Marx he wouldn’t want to belong to an organisation prepared to accept him as a member. Neither he nor his shop received the recognition they deserved, but all people can do now is trot off to the superstore for a bottle of overpriced mediocrity, too young to have character. It leaves St Awful more awful than ever.

If anyone’s out there they won’t find it here

Oscar Wilde described fox hunting as ‘the unspeakable in pursuit of the uneatable’, so perhaps the faceless bodies manning the recently disbanded Ministry of Defence UFO desk were the ‘undeniable in pursuit of the unidentifiable.’

Oscar Wilde described fox hunting as ‘the unspeakable in pursuit of the uneatable’, so perhaps the faceless bodies manning the recently disbanded Ministry of Defence UFO desk were the ‘undeniable in pursuit of the unidentifiable.’

We now have to accept that there are no such things as flying saucers or visitors from outer space, at least not so far as the RAF is concerned as Britain’s X-file personnel have released their final secret file. After spending 60 years investigating all sorts of weird and wonderful sightings, the two-man department decided there are no alien visitors and never have been.

Defence secretary Bob Ainsworth was apparently told in 2009 that ‘no UFO sighting reported has ever revealed anything to suggest an extra-terrestrial presence or military threat to the UK.’ So if the ‘answer is out there’, it won’t be found in the UK.

Things were taken more seriously back in the 1950s when radar threw up odd sightings that could have been either Martians or Cold War threats from the former Soviet Union. The last serious investigation was in 1968. Since then the UFO desk has been described as being like a fire station that always responded to false calls.

I’m not so sure. Many people want to believe in extra-terrestrial live forms like they do the Loch Ness Monster or Lord Lucan. Believers hope that there is a civilisation somewhere that makes a better job of running its planet than we do ours.

News of the demise of our very own Mulder and Scully took me back to the last century when I was in short trousers at St Mary’s School in High Street, Hornsey. At playtime or during the lunch break, I can’t remember which, we saw what we were all convinced was a flying saucer drifting in and out of the clouds high above the school.

It was parachute shaped and appeared to be supporting something underneath that we persuaded ourselves housed a task force of Martians. I remember the science master running round the playground asking us not to look at the object with the naked eye, but through one of the old photographic negatives he was handing out. No one took much notice.

There were headlines supporting what we saw in the evening papers. If my memory can be trusted, it was the main story on the front page, and the official spokesman dashed our schoolboy hopes by saying that the object was a metrological balloon that had drifted off course. No one believed this.

Years later when I was at the Daily Mirror someone said that the former night news editor Dan Ferrari had once sent two reporters to check out a report that the Martians had landed on Primrose Hill.

‘Is this true?’ I asked him after he had been made executive editor. ‘What was the point of sending two reporters to check out the fantasies of some deluded drunk?’

‘It is true. I did send two simply because one of these days your deluded drunk will be telling the truth and there will be little green men everywhere, but if I’d only sent one reporter, I wouldn’t believe him.’

Dan had an answer for everything, some more entertaining than others, but at least part of his mind was open to accept the apparently impossible, while whatever the reported facts, the MoD always denied everything.

There are good reasons why the Cornish often describe the county’s biggest town of St Austell as St Awful.

There are good reasons why the Cornish often describe the county’s biggest town of St Austell as St Awful.

As this is a long established, if not affectionate nickname, it is nothing to do with Richard Curtis’ latest movie, much of which was filmed there. Called ‘About Time’, the film has been so widely bombed that it could have only raised the volume of those who criticise the town.

Making the situation worse is the fact that St Austell has recently lost one of its few remaining assets. I’m referring to the closure and boarding up of the wonderfully unique Delmonicos, my favourite wine emporium, formerly run eccentrically by one of the town’s great characters, David Delmonico.

The ramshackle building has been on the market for some time and, despite the hard-working efforts of two of David’s children, Jason and Suzanne, the days of the off-license were numbered in 2009 when David lost his battle with lung cancer aged 69.

His shop was a remarkable place, a dingy Aladdin’s Cave, grubby and poorly lit, with straw on the floor, faded pictures on the walls, empty wine boxes under your feet and, half hidden on the shelves, the odd brilliant vintage at an affordable price, its label covered in grime. As well as supplying wine you couldn’t get anywhere else, you could buy honey, olives, Scrumpy and spectacular glasses that made good wine taste even better.

David’s heart and soul belonged in 1960s Swinging London, that and his addiction to French cigarettes probably did much to damage his lungs and liver. Apart from a gap in the middle, while he chased a lady or ladies round France, or so he told me, he ran the establishment for over 30 years.

He learned his trade from his father, who was descended from a Swiss family hailing from the village of Mairengo in the Ticino Canton close to Italy. The family name, originally Del Monico, has been associated with food and wine since 1824 when the former sea captain Giovanni De Monico opened a wine shop in New York.

A century later, a parallel London business was opened in Soho’s Old Compton Street, and it was there that David sharpened his taste buds, learned to judge a vintage by the smell of the cork and not only appreciated the difference between Margaux and Moet, but knew the optimum size of the bubbles in the bubbly.

His father sold the business in 1970 and David came to Cornwall with his wife Barbara and three children settling in St Columb to run a pub. But along with nicotine from the Gitanes, wine ran through his veins, and it wasn’t long before he opened in St Austell’s South Street making the town rather less awful than before.

David was not part of the retail establishment. Like Groucho Marx he wouldn’t want to belong to an organisation prepared to accept him as a member. Neither he nor his shop received the recognition they deserved, but all people can do now is trot off to the superstore for a bottle of overpriced mediocrity, too young to have character. It leaves St Awful more awful than ever.

Oscar Wilde described fox hunting as ‘the unspeakable in pursuit of the uneatable’, so perhaps the faceless bodies manning the recently disbanded Ministry of Defence UFO desk were the ‘undeniable in pursuit of the unidentifiable.’

Oscar Wilde described fox hunting as ‘the unspeakable in pursuit of the uneatable’, so perhaps the faceless bodies manning the recently disbanded Ministry of Defence UFO desk were the ‘undeniable in pursuit of the unidentifiable.’

We now have to accept that there are no such things as flying saucers or visitors from outer space, at least not so far as the RAF is concerned as Britain’s X-file personnel have released their final secret file. After spending 60 years investigating all sorts of weird and wonderful sightings, the two-man department decided there are no alien visitors and never have been.

Defence secretary Bob Ainsworth was apparently told in 2009 that ‘no UFO sighting reported has ever revealed anything to suggest an extra-terrestrial presence or military threat to the UK.’ So if the ‘answer is out there’, it won’t be found in the UK.

Things were taken more seriously back in the 1950s when radar threw up odd sightings that could have been either Martians or Cold War threats from the former Soviet Union. The last serious investigation was in 1968. Since then the UFO desk has been described as being like a fire station that always responded to false calls.

I’m not so sure. Many people want to believe in extra-terrestrial live forms like they do the Loch Ness Monster or Lord Lucan. Believers hope that there is a civilisation somewhere that makes a better job of running its planet than we do ours.

News of the demise of our very own Mulder and Scully took me back to the last century when I was in short trousers at St Mary’s School in High Street, Hornsey. At playtime or during the lunch break, I can’t remember which, we saw what we were all convinced was a flying saucer drifting in and out of the clouds high above the school.

It was parachute shaped and appeared to be supporting something underneath that we persuaded ourselves housed a task force of Martians. I remember the science master running round the playground asking us not to look at the object with the naked eye, but through one of the old photographic negatives he was handing out. No one took much notice.

There were headlines supporting what we saw in the evening papers. If my memory can be trusted, it was the main story on the front page, and the official spokesman dashed our schoolboy hopes by saying that the object was a metrological balloon that had drifted off course. No one believed this.

Years later when I was at the Daily Mirror someone said that the former night news editor Dan Ferrari had once sent two reporters to check out a report that the Martians had landed on Primrose Hill.

‘Is this true?’ I asked him after he had been made executive editor. ‘What was the point of sending two reporters to check out the fantasies of some deluded drunk?’

‘It is true. I did send two simply because one of these days your deluded drunk will be telling the truth and there will be little green men everywhere, but if I’d only sent one reporter, I wouldn’t believe him.’

Dan had an answer for everything, some more entertaining than others, but at least part of his mind was open to accept the apparently impossible, while whatever the reported facts, the MoD always denied everything.

A week in Belgium and Germany proved to me that the horsemeat saga is a genuine European story and not merely another example of the Red Tops winding up the nation with an attack on supermarkets.

A week in Belgium and Germany proved to me that the horsemeat saga is a genuine European story and not merely another example of the Red Tops winding up the nation with an attack on supermarkets.

So many people were talking about it, and speculating on whether the culprits were Irish or Polish, that I recalled the part I played in an earlier horsemeat scandal. This started innocuously in December 1980 at Walton Street Magistrate’s Court when their worships were asked to order the destruction of 30 tons of meat stored at the Burlington Road premises of pet food suppliers Anthony Animal Products.

Bruce Cova, chief environmental health officer for the Borough of Hammersmith & Fulham, told West London magistrates that his staff had spied on the company for three days and followed their trucks from Burlington Road to companies that processed food for human consumption. He said the trucks contained carcasses that were ‘most definitely an unusual risk to health’, and not marked with the slaughterhouse stamp required by law showing that they were ‘fit for human consumption’. Some of it was horsemeat from a knacker’s yard; one carcass was cancerous.

Eventually, the owners of Anthony Animal Products, trading since 1975 and with an annual turnover of around £1.5 million before Cova and his team forced them into liquidation, pleaded guilty to 183 summonses issued under the Food Laws.

These were the days before DNA could be used to detect horsemeat in processed food, and when a public analyst told me that once mixed with legitimate beef, flavouring and cereal, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to identify it in a burger, the Daily Mirror did what tabloids do and did it in such a way that, had the truth emerged, added a new dimension to investigative journalism.

Working with fellow reporter Alistair Martin, my job was to obtain horsemeat, get it made into burgers and send it off to a public analyst who would hopefully be fooled. It was inevitable that things would go wrong. First, when my girlfriend found her fridge full of horsemeat, legitimately purchased from a West London pet food supplier, explosive doesn’t begin to describe her reaction. Second, a commercial company had agreed to make burgers to our recipe, but when the management learned about the horsemeat, we were escorted from the premises along with the beef flank and shin we were using, still wearing the white hats they’d given us.

Reporters hate to admit failure and Alistair said the only option was to make the burgers ourselves. Buying freezer knives, cold boxes and an electric mixer was easy, but where could we do the deed? Not at my flat, nor Alistair’s, that was for sure. So we hired a hotel room, turned up the TV and for five hours or so worked until it was done. Making a mess of the room was much easier than cleaning it up; we did our best, but when we left it smelled as we imagined the inside of a horse’s arse would. Luckily, we’d paid cash, so no paper trail.

Our burgers fooled the public analyst, and our investigation, subbed and presented by John Patrick who coined the word Shamburger, was padded out as I recall with sanctimonious claptrap from MPs, environmental health officers, self-righteous food processors and animal welfare wallahs.

Inevitably, there were repercussions, but not from the hapless Horsemeat Hotel. There were herograms, an adjournment debate in the House of Commons in May 1981 and Bruce Cova got a gong. The word Shamburger, incidentally, is now used for a children’s hamburger patty made without meat. Such is the power of the press.

Inevitably, there were repercussions, but not from the hapless Horsemeat Hotel. There were herograms, an adjournment debate in the House of Commons in May 1981 and Bruce Cova got a gong. The word Shamburger, incidentally, is now used for a children’s hamburger patty made without meat. Such is the power of the press.

With a TV movie and now a feature film, we’ve been hearing a lot lately about the film director, Alfred Hitchcock. In a long forgotten newspaper interview, he said he learned about creating suspense when he was a pupil at St Ignatius’ College, at that time in North London’s Stamford Hill.

With a TV movie and now a feature film, we’ve been hearing a lot lately about the film director, Alfred Hitchcock. In a long forgotten newspaper interview, he said he learned about creating suspense when he was a pupil at St Ignatius’ College, at that time in North London’s Stamford Hill.

He was gracious enough not to name the school, a Jesuit establishment with the motto ‘Ad maiorem Dei gloriam’, ‘for the greater glory of God.’ But when Master Hitchcock misbehaved, he was given a chit, usually in Latin, that stipulated the number of strokes or Ferulae he was to receive from a ‘tolly’, traditionally a whalebone wrapped in leather, but later a piece of leather about a foot long shaped like the sole of a shoe.

Hitch didn’t elaborate, but I found out from a St Ignatius alumnus that the sentences were administered daily at four set times. Pupils with chits, effectively requisitions for pain, each had 24 hours to take their orders to the punishment room. There was no escape as carbon copies of the chits were kept and there was a master punishment book. Failure to appear within 24 hours resulted in the sentence being doubled; longer delays saw you dragged from the classroom to face unspecified violence.

First formers were exposed to two Ferulae, one on each hand. Second formers got four, third formers six and so on up to the sixth form when it was 12 on each hand, never 24, but twice 12. Hitchcock said the psychological elements of the punishment were worse than the physical. You had to decide when to report and then to go alone, stand in the queue and listen to the suffering of those in front of you.

I, too, am old enough to have been exposed to corporal punishment, usually rulers and slippers wielded by incompetent teachers who got more pleasure from inflicting pain than imparting knowledge. But far worse for me were the visits to the dentist.

At the clinic in North London where I was forced to go for dental checks, there was a clock on the wall with five or six red numbers in a box below the dial that identified the room you had been assigned when you arrived. When a new victim was required, the clock pinged and one of the numbers jiggled back and forth. Was it your number or somebody else’s? The waiting was unbearable.

Going to the dentist is not at the top of anyone’s social calendar, but in those days it was an inevitable assignation with pain from a drill that got unbearably hot, invariably brandished by a sadistic thug with teeth worse than yours. I can still feel the pain and hear the slapping of the elastic belt that powered the drill, but the worst thing was not the treatment, but like Hitch the agony of waiting that started when the postman delivered your appointment card.

The tension gradually ratcheted up until the night before when you could hardly sleep and then the waiting room with that awful clock tolling the number of the next victim for room three or whatever. While the medieval caning ritual of St Ignatius may have helped Hitch hone his suspense skills, the school dentist did nothing for my journalism.

My local chemist is smaller than Posh Beckham’s wardrobe or the cupboard where Imelda Marcos stored her shoes. This means that everybody in the village knows what we’re suffering from, what’s got better, got worse or was wrongly diagnosed in the first place.

My local chemist is smaller than Posh Beckham’s wardrobe or the cupboard where Imelda Marcos stored her shoes. This means that everybody in the village knows what we’re suffering from, what’s got better, got worse or was wrongly diagnosed in the first place.

Although there’s more room and staff in the pharmacy behind the counter, there’s always a queue in front of it. The customers either sit or stand, their faces wreathed in postures of nonchalance or indifference. This is a sham; they are concentrating intensely on who’s buying what: tampons, condoms, sun cream, zit therapy, foot powder or some miracle conditioner designed to eliminate dandruff or bed-wetting.

So everybody knows what you’ve got or haven’t got, whether your internal plumbing is functioning and your reproductive organs in pristine order. Should something not be right, you can bet your last vitamin that the person behind you in the queue had it before you and discovered that the therapy you’re trying won’t work. Not that they’ll tell you until after you’ve bought it.

The quirky habits and preferred panaceas prescribed by the local quacks are known to everyone in the shop: uppers, downers, sleeping pills, blood pressure capsules, aids to digestion, erection and bowl evacuation. Whether or not this was what the one-time nuclear engineer Stefano Pessina had in mind when he trashed Jesse Boots’ old retail chain in 2007 and used the brand name to turn Alliance Unichem into the world’s biggest chemist shop, I don’t know.

My chemist may be the smallest Boots on the planet so medical secrets in the village are rarer than free car parking at the nearest acute hospital. One’s latest ailment becomes hot news, racing through the community at a pace that leaves Twitter floundering. Illness has become as competitive as the Olympics. Individuals of a certain age boast that they’ve got more wrong with them and take more pills than the guy at the front of the queue waving his prescription. Collecting maladies is the new philately.

To have something seriously unhealthy is like having a more expensive car than the guy next door: ‘You might have had more brain scans than me, but I’ve had more colonoscopies.’

As a result, the debate relating to the confidentiality of health records is academic. Patients don’t just tell the world what they’ve got, it’s their favourite topic of conversation and they boast about it. We may be an ageing nation, but without our hypochondria, ailments, aches and pains we’ be basket cases.

Two characters from the old Mirror Group died recently: Bob Edwards, editor of the Sunday Mirror, who I knew only by sight, and Ronnie Bedford, science editor of both the Daily and Sunday Mirrors who retired in 1985, the year before I moved to the Daily Mail.

At a time when scientific developments happened so fast that it was impossible to keep on top of them, Ronnie brought the basics to the Mirror which, in the 1960s, sold five million copies a day and boasted around 15 million readers. He produced entertaining and informative stories without compromising the science or patronising his readers.

Yorkshire-born Ronnie, who was 90 when he died, taught himself science because he didn’t want to make a fool of himself when he asked questions, more difficult for him than most because he was blind in one eye and had a cleft palate which gave him a speech impediment.

One Space Race scoop came out of a telephone interview with General of Artillery Anatoli Blagonravov in Moscow who in 1957 was involved with putting the first dog into space, Laika. Ronnie had been pressing for an interview, but getting calls from the Soviet Union was a tricky business and there were the additional problems of language and censorship.

Helping Ronnie was the Mirror’s foreign and later diplomatic editor, Freddie Wills (another formidable character, but that’s another story!) who spoke Russian. When questioned, the general admitted that as there was no way of bringing the dog back to Earth, she would have to die in space. Animal stories were the meat and potatoes of the Mirror in those days and Ronnie’s story had readers up in arms.

One afternoon I remember him showing a high-powered group of overseas visitors round the paper. As he reached the news desk he was explaining how this was the nerve centre of the paper when a reporter, rather the worse for alcohol, boiled over and aimed a stream of obscene vitriol in the face of the long-suffering news editor. Ronnie rose above this embarrassing nonsense and dealt with the situation both with tact and humour.

On a human level nothing was too much trouble for Ronnie. When the son of a Mirror editorial executive was involved in a near-fatal road accident, the parents were pressed to permit his heart to be used in an organ transplant. After talking to Ronnie, the parents refused permission for King’s College Hospital, Denmark Hill, to turn off the life support machine and instead sat by their son’s bedside talking to him continually, despite him being unconscious for weeks. The son recovered to become a casual reporter in the newsroom for most of his remaining 32 years.

Ronnie had other talents and was a superb jazz pianist, but I never heard him play. I learned from his Times obituary that the BBC presenter, Paul Vaughan, who was chief press officer of the British Medical Association between 1955 and 1965, said that many doctors were patronising and contemptuous of Ronnie, partly because of his speech defect, ‘but mainly because of their lofty assumption that his newspaper, being a popular one, was incapable of reporting serious issues. How wrong they were. His was a skill born of years of experience as a reporter and of his sharp intelligence’ Vaughan wrote in his autobiography ‘Exciting Times in the Accounts Department.’

Throw Another Guitar on the Fire

I’m still in touch with one school friend. We hadn’t met each other for more than a generation, but he tracked me down through Facebook, and I’m glad he did.

I’m still in touch with one school friend. We hadn’t met each other for more than a generation, but he tracked me down through Facebook, and I’m glad he did.

Back in the high and far off days we traveled all over Europe with our guitars giving impromptu recitals for anyone who listened.

These were not odysseys governed by impoverishment, backpacks and hitched lifts, but masterminded in relative luxury by careful budgeting, rail travel and what now would be three star hotels.

Jeff has just spent a week with me and one damp afternoon we endeavoured to reignite our musical past, a decision devoid of wisdom, one that generated gales of laughter, but very little music.

Our standards are now higher than they used to be, our tastes more sophisticated, but our fingers are not as nimble nor our memories as sharp. Jeff’s fingers protested painfully, while I worried that I couldn’t get my fingers round one particular middle eight, only to discover when we checked that it didn’t have one.

Our standards are now higher than they used to be, our tastes more sophisticated, but our fingers are not as nimble nor our memories as sharp. Jeff’s fingers protested painfully, while I worried that I couldn’t get my fingers round one particular middle eight, only to discover when we checked that it didn’t have one.

We weren’t stupid enough to fancy ourselves as a Barney Kessel-Herb Ellis revival, yet alone Al di Meola and John McLaughlin. Our idea was kick started by tackling jazz with a classical backdrop, Segovia meets Django perhaps, hardly a modest aspiration.

It would have been better to go back to the music we used to play. I remember one piece, Throw Another Log on the Fire arranged for two guitars. We changed the title to Throw Another Guitar on the Fire arranged for two logs.

So repertoire was an issue, but the Real Book helped. We got through Autumn Leaves, Blue Monk, Dearly Beloved, Quiet Nights (Corcovado), Some Day My Prince Will Come and Manha de Carnaval (Morning of the Carnival) from the movie Orfeu Negro (Black Orpheus). In the United States that last tune is often known as A Day in the Life of a Fool. Now there’s a thought. What about two fools?