Bridge faces up to the next challenge

The ways in which playing Bridge* has adapted since the Covid-19 pandemic suggests that the people still playing are more flexible than the game itself.

It wasn’t always the case. In the early days of lock-down there were plenty of duplicate regulars so proud of their technophobia that playing in the same room as a computer was less likely then being dealt 37 high card points.

Suffolk Contract Bridge Association did a lot to spread the word about how easy it was to play online, and sure enough it wasn’t long before even the most ardent Luddite realised that playing online was better than not playing at all.

It threw up some surprising advantages. Playing online you couldn’t revoke, underbid or bid or lead out of turn. There was inevitably a downside: you could double when you didn’t mean to, or pull the wrong card.

By the time lock-down became a thing of the past, the boot, as they say, was on the other foot. People who’d been getting their kicks online were reluctant to return to play face-to-face Some, justifiably, remained terrified of Covid. Others found that they hadn’t really missed the game, at least not by enough to encourage them to venture forth on foggy November evenings. So most clubs struggled to fill as many tables as they used to and there are those struggling to regularly fill four.

Experienced duplicate players knew that the solution was to get more people playing the game and, at least where I play in Norfolk and Suffolk, there are a number of excellent new teaching initiatives.

The next problem is introducing beginners to duplicate and making them feel comfortable with it. Always was a challenge, but ‘no-fear’ groups and supervised practice remain the best solution, although the conversion rate is disappointing. Inexperienced players just find that the weekly humiliation they suffer at the affiliated clubs too hard to take.

New enemy

Now that the drift back to playing face-to-face has probably gone as far as it ever will, other factors have kicked-in. Inflation is now the enemy, not just the cost of fuel used in driving to and from one’s favourite club, but also the increase in the cost of tea, coffee, chocolate bars and biscuits, the hire of premises, the essential accessories like bidding boxes, cards and tables and, for affiliated clubs, the costs necessary for being associated with the English Bridge Union. One successful club told me that the break even of an afternoon session is now 14 tables.

If this is correct it seems inevitable that table money will have to rise. There will be howls of protest and the odd regular may not appear for a couple of weeks. But pause for a moment to reflect on what value for money club bridge is. The game still costs next to nothing; it can even be argued that it’s so cheap that it undervalues the game. Playing online isn’t expensive either.

Sadly bridge has been in decline for a generation or more. Playing cards is no longer a major component of our social lives, millennials sneer at the game as if it were something the cat brought in and enthusiasts like me have got older.

Learning the basics

I learned the basics of bridge while sitting next to my father when he played on Sunday evenings with his two brothers and my grandfather. The stale smell of stubbed-out cigarettes mingled with the remains of a cooling Sunday roast remains stronger in my memory than the standard of card play.

Hovering above the round table and thick baize cloth was a swirling blue cloud of cigarette smoke. Player’s Medium meets Senior Service; my grandfather and his middle son were sixty-plus-a-day men.

I didn’t learn to play the game at these sessions, but I picked up the basics. My grandfather didn’t have much card sense, his three sons did, but their bidding was so appalling and the hand evaluation so misguided that they were forever finagling their way out of disastrous contracts.

When I started earning a living, we played at lunch times for a penny a hundred and that taught me a lot. We growled at every failed finesse, saw optimistic, but doomed three no-trump contracts as a matter of life and death, and blamed every losing score on the incompetence of our long-suffering partner. I thought I could play, but I couldn’t and resented handing over the coppers I regularly lost.

If Bridge was an iceberg, I only understood what showed above the waves. The subtleties of what was going on under the water were lost to me until I discovered the Acol Bridge Club in West Hampstead, run at the time by Chris Dixon and his wife.

The teaching was mastered by South African mathematician Chris Calderwood who showed me how to open a few key doors leading to more competent play. Inevitably this made me a fan of the weak no-trump. But when I later played in the US adapting to Standard American wasn’t difficult.

* If this bridge across the River Adige at Verona is not what you expected, my apologies, but I didn’t want to use the usual montage of playing cards, mischievous jokers or players hunched over a table .

Author Ian Fleming was a member of the Portman Club, where the famous card scene from the 1955 novel Moonraker takes place, but he borrowed the deal from Ely Culbertson, the American writer who helped popularise bridge in the 1930s and 1940s.

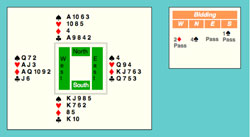

Bond, siting south and partnering his boss M, is playing seven clubs doubled and was out to beat the villain Hugo Drax who was sitting east with a rock-crushing hand including three ace-kings and the king-jack of clubs.

The full deal, known as the Duke of Cumberland hand, was prepared in advance by Bond who switched the cards behind a handkerchief he pretended to use to wipe perspiration from his face.

It is easy to see that Bond’s contract is undefeatable against any defence. Interestingly, the contract is unlikely to have been bid at anywhere other than the Portland, which had banned bidding conventions other than strong two openings and take-out doubles.

Sometimes the best thing about bridge is the opposing pair’s arguments, particularly if you’ve not had the cards.

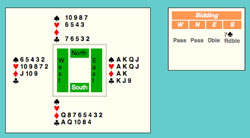

But no row beats this one. It was dealt by a John Bennett in Kansas City in 1931. He was sitting south and partnering his wife Myrtle in a social game with another couple, the Hoffmans.

John opened one spade. West, Mr Hoffman, over-called with two diamonds. Mrs Bennett, North, raised to four spades which became the contract.

Hoffman led the ♦A, but switched to the ♣J when he saw dummy’s singleton. John won the king and drew trumps. Sadly, he went one down.

Myrtle was incandescent, raced to her mother’s bedroom, grabbed a pistol, pointed it at her husband, shot and killed him.

I have no details of what happened next. No matter. She was tried for murder and acquitted. Perhaps there were a few bridge players on the jury.

All these years later the question remains: did Bennett deserve to die of lead poisoning?

He’s a little short on high card points for his opening bid, but she wasn’t strong to raise to game. If Myrtle had known and used the Losing Trick Count she would have counted her eight losers, correctly assumed that her partner had seven losers and deducted the total (7 + 8) from 18 and bid three which he would have passed.

If you look at the cards again you’ll see that John might have saved his life by playing it better. After winning the K♣, he should ruff a diamond with a small trump, lead a trump from dummy and go up with his king.

Follow that with the 10♣. Hoffman would cover with his jack and declarer would win with the ace in dummy.

John should then lead the eight or nine of clubs and ruff it letting Hoffman over ruff if he wanted to.

If Hoffman wins and leads a diamond or heart Bennett’s contract is saved. A trump lead makes it more difficult, but at least declarer would have done his best of it and given himself a chance to land the contract and stay alive.